Briefing

Until now I had only seen books on this subject from scholars, aimed for the academic audience. Matti's book is a mainstream book written like a thriller, so it's a very enjoyable and easy read. Matti is careful to create an interesting story line while sticking to the facts and stating his sources in the appendix, chapter by chapter. He successfully provides the full context in which the fabulous story of the Codex took place and goes back and forth in time delving into the historical relevance of the book and also how it affected so many different people and communities throughout its existence.

The Story (short version + spoliers)

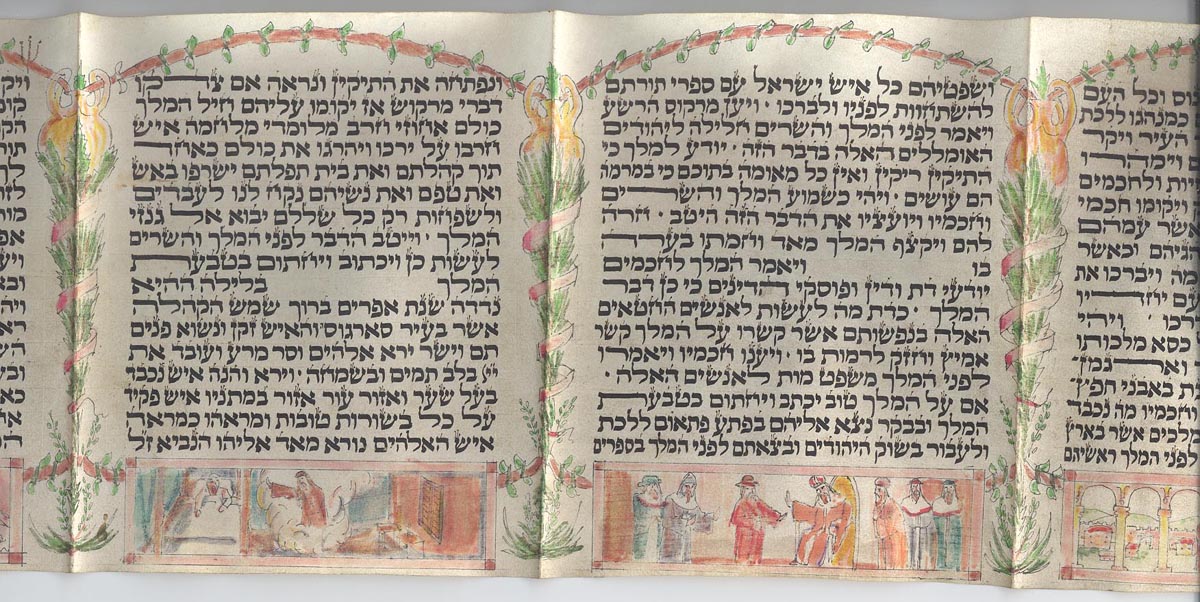

The Ben Asher Codex was written sometime in the 10th century c.e., in Tiberias while the Masoretes were focusing in gathering and establishing the Mesora of vowels, words and missing letters of the Torah. Aaron Ben Asher was the prince of the Masoretes and his codex was widely believed to be the most accurate ever produced, an opinion shared by Maimonides when he saw this book in his own desk in Fustat some centuries later.

The Codex eventually was brought to the Aleppo community, where it was guarded for many centuries until the Arab riots following the creation of the State of Israel. That's when Matti's book gets more interesting.

In 1958, the Aleppo Rabbis sent the Codex with Faham, who was fleeing to Israel via Alexandretta (Turkey). Faham was supposed to give the Codex to the head of the Syrian community in Israel but instead, he gave it to the head of the Aliya Department, Shragai, who gave it to the then President of Israel, Ben Tzvi, a turn of events that triggered a court case a few years later.

The big question discussed in Matti's book is the fact the only about 65% of the Aleppo Codex is in possession of the Ben Zvi Institute in Israel today. What happened to the rest? Interesting to note that the missing pages pretty much cover the whole Bible part of the Codex - the most important section. What we have today is pretty much most of Book of Prophets (Neviim) and Book of Writings (Ketuvim).

To summarize Matti's research, all the possibilities are narrowed down to two options. Either the agent of the Aliya Department in Alexandretta stole the missing parts from Faham, who publicly complained he had been robbed there. Or the Codex was received by President Itzhak Ben Zvi in its entirety but after it was stored in the Institute, someone stole it - other very important manuscripts were reported missing in the early days of the Institute. These two possibilities were and still are potentially very embarrassing for the Israeli authorities so the Institute did their best to cover-up and have always adopted the version that the missing parts were lost in the mob of the Aleppo synagogue, a version that is conclusively not true according to Matti. He also brings good evidence that the missing parts were actually in the manuscript black market as late as 1985, in a colorful story featuring the Bukharian jeweler Shlomo Moussaief (see here a NYT Magazine article based on Matti's book with some additional reporting)

|

| Sample page of the Aleppo Codex |

:(משנה תורה" (הלכות ספר תורה פרק ח הלכה ד"וספר שסמכנו עליו בדברים אלו הוא הספר הידוע במצרים שהוא כולל ארבעה ועשרים ספרים שהיה בירושלים מכמה שנים להגיה ממנו הספרים ועליו היו הכל סומכין לפי שהגיהו בן אשר ודקדק בו שנים הרבה והגיהו פעמים רבות כמו שהעתיקוּ ועליו סמכתי בספר התורה שכתבתי כהלכתו

But aside from the Megillat Esther issue, some communities have custom of reading the Shabbat's Haftarot from scrolls and adopting the Aleppo Codex would also bring disputes. This custom was instituted by the Gr"a, one of Judaism's brightest minds, and anybody living in Jerusalem has seen this numerous times - many of the early settlers of Jerusalem were disciples of the Gr"a and in general, the holy city follows his customs. The Gr"a instructed the scribes to use what is known in the field as the Berditchev tikkun layout, a puzzling book that doesn't conform with the Aleppo Codex layout in the Neviim and Ketuvim.

So in no time, there was a battle between the Jerusalem-based disciples of the Gr"a, who always wrote their Na"ch scrolls according to the Gr"a's Berdichev tikkun versus Bnei Brak, one of Israel centers of Torah learning and a city who generally doesn't follow the Gr"a customs. The Bnei Brak-based groups favored the use of the Aleppo Codex, as it is undeniably the most accurate one.

So any scribe trying to buy a Tikkun, his personal codice to guide him in layout and spelling, will find different options depending where he goes. In Jerusalem, the shops will usually sell Tikunim following the instructions of the Gr"a while in Bnei Brak you will see some Aleppo Codex options too. But even more than that, there's a war of words betweeen the two camps, and when I got my Tikkunim, I snapped some pictures from both sides' claims. See below, the first two are from Talmidei HaGra and the last is from the Aleppo Codex backers.

|

So as you see, the 65% of what we have from the Crown already brought considerate challenges and disputes in the Safrut world and not all have backed its adoption. You can only begin to imagine what would've happened if we had all the Codex, more specifically , the Bible part. While the usage of scrolls for Na"ch is limited, all Jewish communities and synagogues have numerous Torah scrolls and continue to write new ones every day. If the Aleppo Codex for the Bible would be available, I anticipate that we would have a similar, but much more heated war of words and I wonder how many communities would start adopting the Aleppo Codex for their own scrolls.

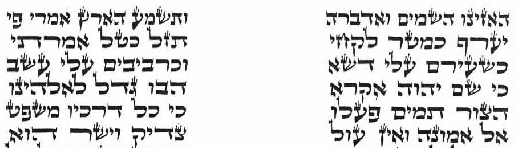

This would imply that the Ahskenazi structure of Shirat Hazinu is problematic. Halacha says that if there's a pause (

This would imply that the Ahskenazi structure of Shirat Hazinu is problematic. Halacha says that if there's a pause (