I write slowly and only in my free time, so I was expecting it would take me many years to finish the Torah. But something interesting happened.

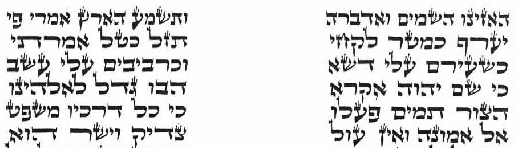

A few months ago, I was spending my summer vacation in a seaside resort, and I got an Aliyah in the local Shul - the fifth portion of Parshas Korach, Chamishi. The Baal Koreh finished the reading, and as I was closing the Sefer Torah to make the final blessing, the corner of my eye say something strange with the last word. I still (mistakenly) made the Bracha after the Aliya but I opened the Torah once again and I realized that there was a mistake that looked like this:

An untrained eye would not spot the problem, as the Sefer Torah's writing was very solid and it was regularly used for over 30 years in that Shul. My question was, and still is, when this mistake happened - was the Sefer Torah pasul for a long time already?

I later came back to the Shul to take another look at it with the Gabbay and I came to the conclusion this was an impurity that found its way in this letter. It was a clear case of bad luck - wrong thing at the wrong place at the wrong time - and this "ink" fell in the worst place possible, changing the form of the letter (Tzurat Haot). Once the letter's form is compromised, the Halacha is that this letter becomes invalidated, even tough it was originally written properly, and consequently the whole Torah is Pasul.

I still couldn't believe this happened - it's the first time I caught a potential psul in a Torah - and I kept touching this strange connector, when suddenly I was able to clip away the connector, restoring the letter to what it was - a Hey. Welcome back, Hey.

Problem solved? Not at all.

This seemed to be a classical case of fixing a letter via Chok Tochot, which is forbidden. Chok Tochot means shaping a letter not by writing it, but by erasing parts of another letter. Imagine you write a big square of black ink, and slowly you "sculp" a letter by erasing parts here and there - that's Chok Tochos and that's a classical act of invalidation according Halacha. By clipping away the connector, I created a Hey from a modified Tav - not by writing it but by "playing" with the Tav. If this was the case, I would have to remove the Hey and rewrite it.

In the other hand, it could be that the connector never actually modified the Hey, since it was kind of a sticker that could be removed (as I did!). If that was the case, perhaps the Torah was always Kosher and it would require no action.

We asked a knowledgeable Dayan, who decided that it was necessary to erase and re-write the Hey - the Torah was pasul indeed. I asked the Shul's board to let me fix it, so I could be the Sofer restoring this Torah by fixing just one letter. This reminded me a concept brought down in the Talmud in Menachot:

וא"ר יהושע בר אבא אמר רב גידל אמר רב הלוקח ס"ת מן השוק כחוטף מצוה מן השוק כתבו מעלה עליו הכתוב כאילו קיבלו מהר סיני אמר רב ששת אם הגיה אפי' אות אחת מעלה עליו כאילו כתבו R. Yehoshua bar Aba: One who buys a Sefer Torah is like one who seized a Mitzvah from the market (Rashi - it is a bigger Mitzvah to write it himself; Rema - he does not fulfill the Mitzvah);If he wrote a Sefer Torah, it is considered as if he received it from Sinai.

A simple reading of this Gemara suggests that any Sofer fixing a Sefer Torah that is pasul is actually performing the Miztva of writing a Sefer Torah - even if the Torah is not his (for example, a communal Torah scroll or a scroll that belongs to a library). After all, he is "creating" a Kosher Torah Scroll.Rav Sheshes: If he corrected even one letter, it is considered as if he wrote it.

The Tosafists immediately weigh in this issue and write explicitly that the Gemara's last clause is not an independent one; it is the the continuation of the previous cases and it talks about someone who bought a Sefer Torah, which was invalid, and fixed it and only in this case, the Talmud is saying that this is equivalent to actually writing a whole Torah. See here verbatim:

אם הגיה בו אפי' אות אחת. פירוש בס"ת שלקח מן השוק לא נחשב עוד כחוטף מצוה

Sounds like Tosafot is explaining this Gemara in order to specifically dispel the possibility ("Hava Amina") I raised above, and would obviously rule that a Sofer fixing someone else's Torah is not fulfilling the Mitzva of writing a Sefer Torah.

This view is the mainstream approach among the classic commentators, and it is the universally accepted Halacha. However, the Mishnas Avrohom, an important early work on the laws of Safrut written by one of the Levush's children, brings down (see here) sources that apparently award the fixer the Miztva of writing the scroll even if the scroll belongs to someone else - precisely the idea we expounded above. The Mei Yehuda also brings other important sources agreeing with this idea. Therefore, basing myself in this minority view, I can say that when I rewrote the Hey and validated the Shul's Torah, I somehow got the Mitzva of writing my own Sefer Torah!

But realistically speaking, if I want to fulfil this magnificent Mitzva properly, I have to continue writing my own Sefer Torah, and I'm still at it. Nevertheless, this incident was a good opportunity to expand on the concept of what invalidates a scroll, Chok Tochos, how to fix it and the significance of writing even one letter in a scroll - perhaps this can also explain, as the Mei Yehuda writes (here), why people are careful to write at least one letter before the Sofer completes a new Torah Scroll (see my original post on this here). Even a small letter matters and it can make a very big difference.

This would imply that the Ahskenazi structure of Shirat Hazinu is problematic. Halacha says that if there's a pause (

This would imply that the Ahskenazi structure of Shirat Hazinu is problematic. Halacha says that if there's a pause (