One of the most popular Judaica items today is the Pitum HaKetoret, an excerpt of the Tamud in Kereisos 6, written like a Sefer Torah in parchment in various layouts, often times together with a Menorah-shaped Lamnazeach alongside it. This is probably the cheapest Safrut item a person can buy, and it can be used daily in Shachrit and Mincha prayers.

One of the most popular Judaica items today is the Pitum HaKetoret, an excerpt of the Tamud in Kereisos 6, written like a Sefer Torah in parchment in various layouts, often times together with a Menorah-shaped Lamnazeach alongside it. This is probably the cheapest Safrut item a person can buy, and it can be used daily in Shachrit and Mincha prayers.

This item always puzzled me. It’s an oddity to write Talmudic passages in parchment like a Torah or Megillot - there’s no precedent to this. The Ketoret has two passages of the Torah, and then a Baraita expanding on all the ingredients of the Ketoret as it was done in the Temple.

Before addressing this minhag of writing the Ketoret in Klaf, let’s step back and understand why we recite the Pitum Haketores every day and it’s importance.

The Beis Yosef (OC 133) writes that in the Siddur of Rav Amram Gaon (9th century) there was the full passage of Pitum Haketoret as in our Siddurim today - a testament of how old is the custom of reciting this passage in the prayers.

It would seem that its importance is similar to all the other passages about the Temple services in our daily prayers - as we cannot perform them in our days, we recite them and it's considered like we made the sacrifices, or in the words of the prophet Hoshea, וּֽנְשַׁלְּמָ֥ה פָרִ֖ים שְׂפָתֵֽינוּ, "instead of bulls we will pay with our lips" - our prayers are today's sacrifices.

But there's a stringency in the Ketoret, already mentioned by the Rama (16th century - source here), that a person must read it from a written text but not from memory, because of the halacha that in the times of the Temple, forgetting any of the ingredients of the Ketoret incense was punishable by death. As mentioned, we recite the Pitum Haketoret in order to emulate the Ketoret preparation, therefore a person must make sure not to forget any ingredients, and reciting it by heart will inadvertently cause you to skip something some day.

In fact, this is why Sephardim to this day, and Belz Hassidim, are careful to count with their fingers each ingredient while reciting the Pitum Haketoret - an extra layer of protection against skipping an ingredient (the source of this Minhag is Rabbi Chaim Vittal, the Arizal's prime disciple, in his Pri Etz Haim - here). See video below where you can visualize this Minhag, as performed by an Iraqi Jew.

The emergence of the Zohar (see Vayakhel) and Kabbalistic minhagim in the 16th century brought the concept of reciting the Pitum Haketores to a whole new level, highlighting its esoteric value and protective properties (specially against plagues; that's why many are reciting it in the current Covid-19 epidemic, see article) to those who recited it, with the note that “there’s nothing as dear to Hashem as the Ketoret”.

The Arizal popularized this concept and encouraged his followers to recite this passage twice daily, in Shachrit and Mincha, with maximum concentration, with the caveat that it should only be recited during the day but not in nighttime because of Kabbalistic considerations (although the Rama, mentioned above, and others specifically advised to recite it after Maariv).

In our Siddurim today, the Ketoret is printed twice in Shachrit - once in the very beggining, before Hodu, and a second time in the very end before Aleinu, but this came about because of conflicting opinions about the optimal placement for the Ketoret in the morning prayer, and Siddur printers opted to follow both opinions. Many people only recite it once in Shachrit, usually at the end, and once again before Mincha.

Rabbi Moshe ben Machir, another famous Kabbalist who lived in Safed at the same time, wrote in his important work Sefer Hayom (source here);

החושש עליו ועל נפשו ראוי להשתדל בכל עז בענין הזה ולכתוב כל ענין הקטורת בקלף כשר בכתיבת אשורית ולקרות אותו פעם אחד בבקר ובערב בכוונה גדולה ואני ערבHe who is afraid for his life, should focus all his might in this topic and write it in a Kosher parchement, in Ktav Ashuri script, and recite it once in the morning and again in noon with great concentration. And I am the guarantor.

This is the earliest source recommending the writing of the Pitum Haketores in parchment, with Safrut lettering. Note his unusual wording "and I am the guarantor", meaning that he is personally attesting the protective powers of this passage if recited in the prescribed manner.

The Kaf Hachaim (19th century - source here), respected Kabbalist and Chief Rabbi of Turkey, also brings that the Ketoret "should be written like a Sefer Torah and it will bring him constant wealth", in addition to many other segulot associated with the Ketoret.

But there aren't many more sources to the Minhag of writing the Ketoret in klaf, and while all Kabbalists highlight the importance of the Ketoret, almost no one writes anything about writing it specifically in Klaf like a Torah Scroll. Perhaps this connected to the prohibition of writing a Torah scroll with only a few scattered passages, mentioned in the Talmud (Gittin 60a) and seemingly undisputed in practical Halacha, as quoted by the Rambam:

מֻתָּר לִכְתֹּב הַתּוֹרָה כָּל חֻמָּשׁ וְחֻמָּשׁ בִּפְנֵי עַצְמוֹ וְאֵין בָּהֶן קְדֻשַּׁת סֵפֶר תּוֹרָה. אֲבָל לֹא יִכְתֹּב מְגִלָּה בִּפְנֵי עַצְמָהּ שֶׁיִּהְיֶה בָּהּ פָּרָשִׁיּוֹת. וְאֵין כּוֹתְבִין מְגִלָּה לְתִינוֹק לְהִתְלַמֵּד בָּהּ. וְאִם דַּעְתּוֹ לְהַשְׁלִים עָלֶיהָ חֻמָּשׁ מֻתָּר.:It is permitted to write the Pentateuch, each book in a separate scroll. These scrolls have not the sanctity of a scroll of the Law that is complete. One may not however write a scroll containing some sections. Such a scroll may not be written for a child's instruction. This is permitted, however, where there is the intention to complete the remainder of the book.

The Shulchan Aruch follows suit (here), therefore casting serious doubts about the permissibilty of writing the Pitum Haketores, which has a few Biblical passages, in parchement like a Torah Scroll. It's perhaps no coincidence that we have no precedent to writing something like the Ketoret in Klaf, and the question is not anymore why there are so few sources to this Minhag but how is it at all permitted.

The Shulchan Aruch follows suit (here), therefore casting serious doubts about the permissibilty of writing the Pitum Haketores, which has a few Biblical passages, in parchement like a Torah Scroll. It's perhaps no coincidence that we have no precedent to writing something like the Ketoret in Klaf, and the question is not anymore why there are so few sources to this Minhag but how is it at all permitted. This prohibition is also applicable in everyday issues like writing Psukim in wedding invitations, which are commonly adorned with passages like אִם לֹא אַעֲלֶה אֶת יְרוּשָׁלַֽיִם עַל רֹאשׁ שִׂמְחָתִי or Kol Sasson veKol Simcha (see picture). Many scupulous individuals avoid writing it, or modify the passages slightly in order to avoid writing a scattered Pasuk (see here for an interesting article discussing this and other Halachic problems involved in Psukim in wedding invitations, by Rabbi Kaganoff) - and the Pitum Haketores, written in parchement and Ktav Ashuri like an actual scroll, would be even more problematic if written exactly like a Sefer Torah.

Perhaps the supporters of writing Ketoret in Klaf today utilize the Halachic heter of Es Laasos Lashem, which justifies writing Oral Torah even though there's a different, all encopassing prohibition of writing it in any form. This Halachic justification, which overrides the prohibition on the grounds that Chazal at the time of the Mishna felt that there was no other way to preserve the Torah, could be extended to the idea of writing a small scroll like the Pitum HaKetoret. This possibility is brought down by the Mizahav Umipaz (link), which has an excellent overview about many of the issues raised in this article.

Any way you slice it, it's difficult to find Halachic precedent to justify writing the Ketoret like a Sefer Torah and I haven't found many responsa on this issue. Perhaps this custom was not as widespread in previous generations. I was pointed to Rav Ovadia's responsa , in his magnum opus Yebia Omer (ח"ט יו"ד סי' כג) who disapproves this minhag (rather surprising, as it goes against the Kaf Hachaim, and Rav Ovadia was often careful to justify established Sephardic customs) but says that if you already have a Ketoret written in Klaf, it's no problem to read from it - a paradoxical answer (see this link for a quite and discussion about Rav Ovadia's ruling).

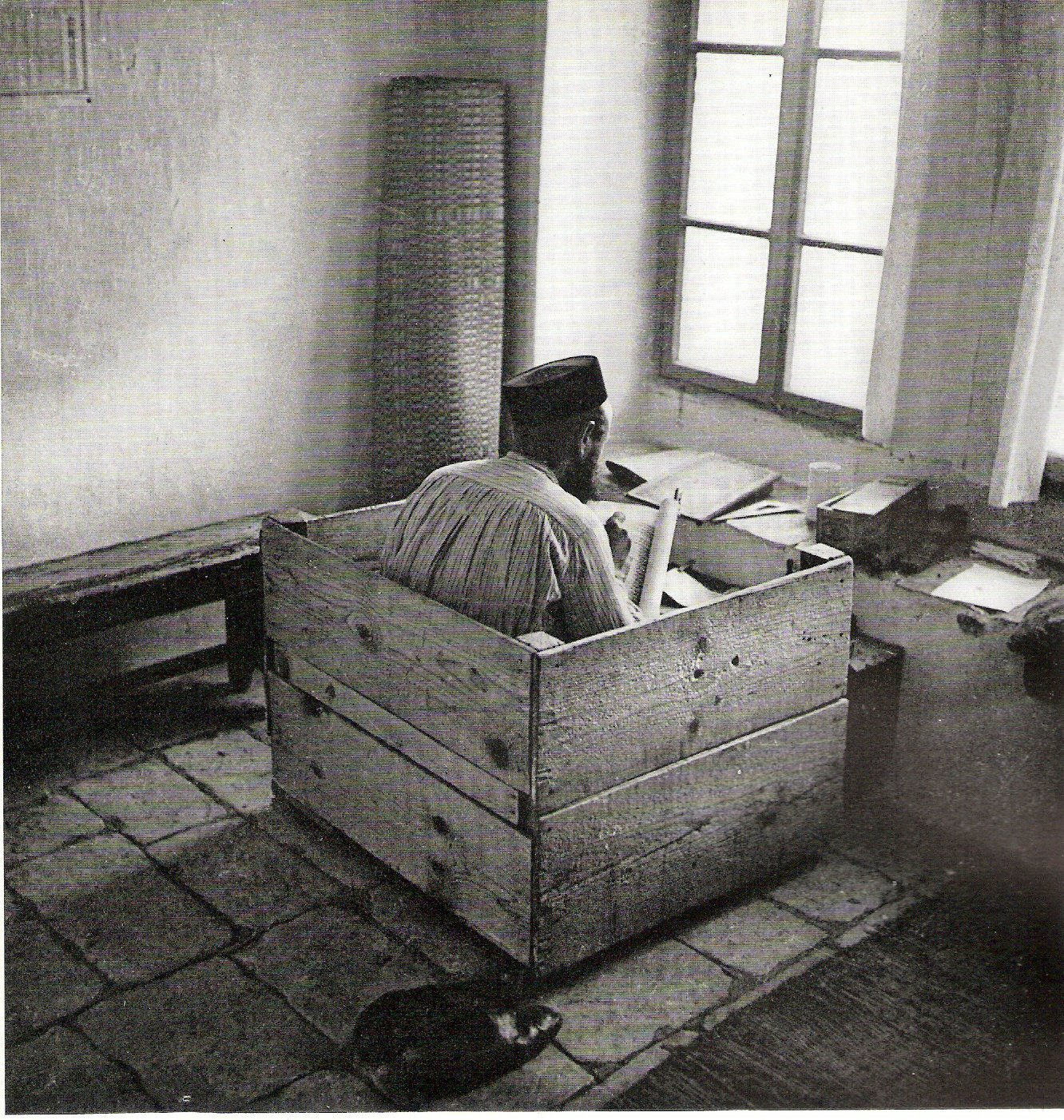

In practice, the Pitum Kaketores today is commonly a scribes' inauguration work because the Halachot of Torah, Tefillin and Mezuza do not apply to this novel scroll and therefore it's a good way to practice while not being afraid of making mistakes. One of my first works was indeed a Pitum Haketoret and guess what, I skipped a line but never thought it was a big deal (see picture). But as we have seen, there's one Halacha about this scroll that is more stringent than any other scroll - a Sofer cannot skip a word from the Ketoret ingredients lest he will be punishable by death! Baruch Hashem, it turns out that I skipped one of the very last lines, so without knowing at the time, I actually dodged a bullet by sheer luck.

After I got familiar with the issues discussed above, I have a whole different level of appreciation for the Pitum Haketores recitation - it is really a standout feature of our daily prayers. However, the sad reality is that, as the Rama predicted, people run through this tefillah because it is at the end of morning prayers and everyone is rushing for their daily schedules. I don’t remember last time I davened in a Minyan that gives enough time to say it word by word - the Chazzan will always rush towards Aleinu. And as noted by the Kaf Hachaim, if recited without the proper focus and rhythm, it has no esoteric value and even worse, it can even cause a major transgression of skipping a word from the Ketoret. The Ein Maavar Yabok (17th century) writes that the Chazzan must recite the whole section aloud just like the Shemone Esre, in order to make sure the Shul will have enough time to recite the Ketoret.

Notwithstanding the obscure origin of this Minhag, the reality is that it is very widespread today and one can find a Pitum Ketoret in hanging in many synagogues around the world and also in private people's tefillin bags - Ashkenazi and Sephardi. While the Halachic weight seems to be against this practice, some authorities try to find Halachic loopholes (see Mizahav Umipaz here for some suggestions) in order to justify this widespread Minhag, which could perhaps be referred to as a "Minhag Israel Torah Hi" - a well established Minhag can have validity even if it's not well justified. However, the most important thing to discuss is not whether the Ketoret should be written in parchement or not. What is crucial is having the proper state of mind, and knowing how important the Pitum Haketores is in our daily prayers.