"בתורתו של רבי מאיר מצאו כתוב, "והנה טוב מאד" (בראשית א, לא) - "והנה טוב מות" (בראשית רבה וילנא, ט, ה)

"ויעש ה' אלקים לאדם ולאשתו כות

נות עור וילבישם" (בראשית ג, כא). בתורתו של ר' מ איר מצאו כתוב: "כותנות אור" (בראשית רבה תיאודור-אלבק, כ, כ א)

This Medrash says that Rabbi Meir’s Torah had some variant readings distinct from our mainstream Mesora. Instead of טוב מאד, his text was טוב מות; instead of כותנות עור, he had כותנות אור.

This is a puzzling and difficult concept to understand. The Talmud (Eiruvim 13a) says that Rabbi Meir was an expert Sofer, who learned by the foremost leaders of his generation - Rabbi Yishmael and Rabbi Akiva.

While a small variant reading of עור and אור is a relatively minor issue, Rabbi Meir’s other variant - טוב מות - seems completely different and unrelated to the mainstream text. What can be the connection between טוב מאד and טוב מות, which was highlighted by Chazal as a point of variance between two traditions ?

I usually like to follow a somewhat scholarly approach in my posts, but to answer this question I will turn to Derash.

There are many comments about the connection between עור and אור, mostly based one the famous Zohar that originally the skin of Adam was translucent, full of light, but after his sin it turned like our skin, hence the connection between the words.

Exploring this concept further, I've heard in the name of Reb Tzadok Hacohen |(please comment if you have the written source) that specifically Rabbi Meir had the unique ability to understand the ultimate purpose of everything in this world and how all connects in a meta-physical reality. In his perception, כותנות עור was very clearly not just leather clothes but clothes hiding a spiritual light and Rabbi Meir could perceive that in all creation at any given time - not only before Adam’s sin. For Rabbi Meir, all creation was connected and he saw how that worked.

What about the connection of מאד and מות?

If we take Reb Tzakok’s insight a step further, that our traditions and Rabbi Meir's reflect two different worldviews, let’s analyze why this specific variant has been highlighted. Both מאד and מות start with the Mem, the middle letter of the Hebrew alphabet and the letter representing the present time. We can see that Rabbi Meir could start from the Mem and perceive the very end-objective of everything, and this is codified in the word מות, going from the Mem directly to the Tav - the final letter of the alphabet and the ultimate goal.

However, our perception is not like Rabbi Meir’s, and we cannot connect all the dots of the world around us. The best we can do is try to go back to how things started and from there try to find meaning. That’s the מאד - starting from the Mem, going to back to the Aleph which is the symbol of Hashem’s unity and then to the Daled, which is the letter highlighting how Hashem interacts with our world. That’s our approach to dealing with this world (see more about this concept in Ari Bergmann's podcast here).

Hence we find a possible connection between the two readings and how they represent differing worldview approaches, as explored by Reb Tzadok. It turned out to be that Rabbi Meir’s approach was not tenable, and the mainstream text is indeed טוב מאד.

Of course, this discussion leads to the question of how the Torah text can have variant readings, which in turn challenges the Rambam’s view that our Masoretic text is the “immaculate text”, without any changes through time. To read a great piece on this, which requires a more scholarly approach, see this great post at the Kotzk Blog, discussing what would happen if we would find an authoritative old scroll that differs from our accepted Masoretic text.

One possible conventional answer is brought by the Torah Temima (source), who writes that some understand the Medrash to be referring not to Rabbi Meir’s actual Torah Scroll but his written novelea, where he expounded the meaning of the Torah text. Or perhaps his marginal glosses written around his personal Torah Scroll. In other words, he had no actual variant Mesora.

Be it as it may, as for the connection between מאד and מות, we have found that these variant readings can be understood not as a mere curiosity; it’s a hidden message highlighted by the Medrash, and up to us to understand its message.

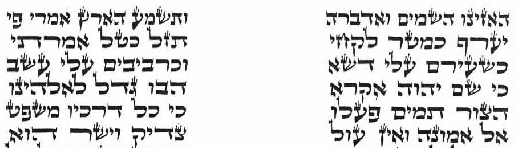

This would imply that the Ahskenazi structure of Shirat Hazinu is problematic. Halacha says that if there's a pause (

This would imply that the Ahskenazi structure of Shirat Hazinu is problematic. Halacha says that if there's a pause (