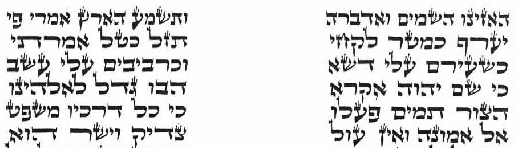

One of the few columns that stand out in a Sefer Torah is Shirat Hayam, with its “brick and mortar” shape, and Haazinu, with its “two towers” shape. As a general rule, the Torah Scroll has small blank spaces scattered around every column, and they serve to delineate paragraphs and to provide to the reader a moment of reflection.

I have written about the importance of the correct placement of these blank spaces, called in Rabbinic parlance Parshiot Petuchot and Setumot, in an older post and I encourage you to look there too.

But as a whole, the Torah layout is a continuous prose in all its columns, save the two instances mentioned above. Both are songs, and it seems that the unusual layout is intended to highlight their poetic structure. Commentators offer more esoteric explanations, that the two towers Haazinu layout allude to the downfall of the wicked, which are mentioned in one of the stanzas (this explanation is also applied to the two tower layout of Haman's wicked sons in Esther's Scroll, discussed here).

The Rambam dedicates many pages to the correct layout of all Parshiot in the Torah, and he writes that Shirat Haazinu should be divided in 70 lines. Look at the text in Sefaria:

צוּרַת שִׁירַת הַאֲזִינוּ - כָּל שִׁיטָה וְשִׁיטָה יֵשׁ בָּאֶמְצַע רֶוַח אֶחָד כְּצוּרַת הַפָּרָשָׁה הַסְּתוּמָה. וְנִמְצָא כָּל שִׁיטָה חֲלוּקָה לִשְׁתַּיִם. וְכוֹתְבִין אוֹתָהּ בְּשִׁבְעִים שִׁיטוֹת. וְאֵלּוּ הֵן.

That’s indeed how our Torahs (see example pic at the top of this post) are structured - both Ashkenazi and Sephardi scrolls - in accordance to the Rambam’s account and we would expect that to be the case, as the Rambam had in his possession the prized Aleppo Codex - the most authoritative codex according to our tradition.

The Yemenite Jews have a handful differences in their Mesora of the Torah text, minor differences in the spellings but one very visible variance stands out. Their parshat Haazinu is written in 67 lines, unlike Ashkenazi and Sephardic scrolls.

When looking closely, they have a different arrangement in three stanzas, which are merged together forming a longer, more squeezed, line. Because of that, the layout of their Haazinu column is much less homogenic and the “two towers” are not perfectly aligned. See a picture of the Yemenite tikkun:

We all know the Teimanim follow the rulings of the Rambam closely, which in turn begs the question - how do they reconcile their Mesora with the Rambam?

Let’s turn to the Aleppo Codex again. As I discussed elsewhere, this codex is attributed to the Masorete Ben Asher, and was salvaged from the Aleppo synagogue pillaging in the 1947 Arab protests against the establishment of the State of Israel..

The local Sephardi community guarded the Codex closely, and very few outsiders managed to find a way to look at it. One of the few was Humberto Cassuto, a famous scholar who wanted to investigate if this Codex was indeed the one attributed to the Ben Asher lineage. Professor Cassuto was granted limited access and couldn’t study it throughly, but he cast doubt at the provenance of the Codex because he saw that the Haazinu of the Codex had 67 lines, and not 70 lines as discussed in the Rambam’s Mishne Torah.

Many scholars started to investigate this finding. It turned out that the Yemenites have a different reading of the Rambam and in their manuscripts it states that Haazinu has 67 lines - just like Professor Cassuto observed in the Codex, except he wasn’t aware that his own Rambam’s edition was corrupted. The very feature Prof Cassuto found to be suspicious turned out to be the best proof of the authenticity of the Codex. An early manuscript of the Rambam from Oxford's collection has the same version as the Yemenites, and that's how Mechon Mamre has it in their online Rambam:

יא צוּרַת שִׁירַת הַאֲזִינוּ (דברים לב,א-מג)--כָּל שִׁטָּה וְשִׁטָּה, יֵשׁ בְּאֶמְצָעָהּ רֵוַח אֶחָד כְּצוּרַת הַפָּרָשָׁה הַסְּתוּמָה, וְנִמְצֵאת כָּל שִׁטָּה חֲלוּקָה לִשְׁתַּיִם; וְכוֹתְבִין אוֹתָהּ בְּשֶׁבַע וְשִׁשִּׁים שִׁטּוֹת. וְאֵלּוּ הֶן

Although almost all the Chumash part of the Codex was destroyed (or hid away, as claimed by Matti Friedman’s great book discussed here), the Haazinu pages observed by Prof Cassuto have survived and can be seen in the Israel Museum and online. See it here:

The Yemenites kept the Rambam’s proposed Mesora (save one puzzling, small variance towards the end of Haazinu in the stanza starting with "Gam Betula" which the Yemenites start with the preceding "Gam Bachur" - the similar words seemed to have caused this confusion but perhaps there's a better explanation I'm not aware of).

The Ashkenazi and Sephardi did not, and there was an obvious attempt to cover up the discrepancy between their tradition (70 lines) and the Rambam’s (67), and while a few expert scholars (like 16th century Menachem di Lonzanu, in his popular work Or Torah - see here at the bottom) eventually noted conflicting versions of the Mishne Torah, this caused much confusion and eventually most scholars became convinced that the versions of the Mishne Torah with 67 lines were simply wrong because they didn't comply with the vast majority of the existing scrolls.

The Ashkenazi and Sephardi structure of 70 lines has its source in the Masechet Sofrim 12 (exact link here, where it states the first word of every line totaling 70), which is one of the handful small tractates found in the Babylonian Talmud and is generally attributed to the Gaonic period. Even though the Codex was housed in Aleppo - a major Sephardic center - for a very long time, the Sephardic world adopted the 70 line tradition which was the most prevalent and based their text in Rabbi Meir Aboulafia’s (who was an opponent of the Rambam) authoritative compendium Masoret Seyag Latorah - not the Aleppo Codex. Ironically, the Aleppo community guarded the Codex as its prized relic while following another Mesora for the Haazinu parsha (credit for the great Prof Marc Shapiro for this insight).

A few scholars have attempted to conduct studies of Torah Scrolls from different pre-war communities in regards to their Haazinu structure, in order to discover how prevalent was the 70 line structure. Scholars have found that there were more than two options - some scrolls had a little more than 70 lines while others fewer than 67, some had no unique structure at all, while others had Haazinu in the brick and mortar layout of Shirat Hayam! It seems like the scribes generally knew that Haazinu had a special layout but had limited knowledge of how to write the special structure.

The difficulty in regards to Haazinu stems from this Talmudic passage in Megillah:

אָמַר רַבִּי חֲנִינָא בַּר פָּפָּא, דָּרֵשׁ רַבִּי שֵׁילָא אִישׁ כְּפַר תְּמַרְתָּא: כּל הַשִּׁירוֹת כּוּלָּן נִכְתָּבוֹת אָרִיחַ עַל גַּבֵּי לְבֵינָה חוּץ מִשִּׁירָה זוֹ וּמַלְכֵי כְנַעַן, שֶׁאָרִיחַ עַל גַּבֵּי אָרִיחַ וּלְבֵינָה עַל גַּבֵּי לְבֵינָה. מַאי טַעְמָא — שֶׁלֹּא תְּהֵא תְּקוּמָה לְמַפַּלְתָּן —Said Rabbi Hanina bar Pappa, Rabbi Shila, a man of the village of Temarta, expounded: all songs -- all of them -- are written a small brick (writing) above a brick (blank space), and a brick above a small brick, except this song (Sons of Haman) and [the song of] the kings of Canaan, which are a small brick above a small brick and a brick above a brick.

Note that Haazinu is not mentioned as one of the exceptions, and you could infer from this passage that Haazinu should be written like all other songs - in a brick and mortar fashion! That is the likely explanation of why some older scrolls have this feature - perhaps some scribes based themselves in the simple understanding of this Gemara. The Noda Biyuda discusses the Halachic status of this layout and based on this understanding he tries to find a way to not invalidate these scrolls. See below how a Haazinu in brick-and-mortar shape would look like:

However, the Masechet Sofrim is categorical, and clearly states that Haazinu is not to be written like Shirat Hayam, and that's the normative Halacha - even though the Masechet Sofrim is from the Gaonic period and hence, theoretically less authoritative than the Talmud which seems to imply that Haazinu should be written like all songs - in brick and mortar layout.

Professor Mordechai Breuer, one of the leading experts of the Aleppo Codex, attempted to harmonize the Talmudic passage above with the ruling of the Masechet Sofrim by developing the idea that Haazinu is not a real Song/Shira, and therefore not the subject of the Talmud's discussion above. In other words, Haazinu is in a category of its own and it's unlike Shirat Hayam, Bnei Haman and Shirat Devorah (see here page 23 for further discussion and a great resource in this topic).

The complexity of this Talmudic passage is the best explanation of why there's not one single option when it comes to writing Haazinu - the Talmud is ambigious and the scribes had a tough time getting it right.

However, scholarly research has shown that in both Ashkenazi (Prof Goshen-Gottstein) and Italy (see Prof. Orlit Kolodny here with more details), the most common layout was undoubtedly the 70 line structure, as per the Masechet Sofrim. Less than 10% of the 250+ scrolls surveyed have the 67 layout, which means that the Rambam/Yemenite Mesora was actually not very popular. While the Rambam tried to push for the 67 Mesora in his very detailed account of how Haazinu should be written, it seems clear that already in his time this Mesora was not dominant and his initiative did not gain much traction in the wider Jewish world. The fact that the Rambam's manuscript was censored to conform with the 70 line Mesora is an indication that there was a push back to the Rambam's directive, and the censorship (see more about this in Prof Marc Shapiro's "Changing the Immutable") was a very efficient way to safeguard the prevalent Mesora of the Masechet Sofrim - it even fooled an expert scholar like Prof Cassuto.

This would imply that the Ahskenazi structure of Shirat Hazinu is problematic. Halacha says that if there's a pause (

This would imply that the Ahskenazi structure of Shirat Hazinu is problematic. Halacha says that if there's a pause (