This highlights how important this intricate song is in relation to the whole Torah.

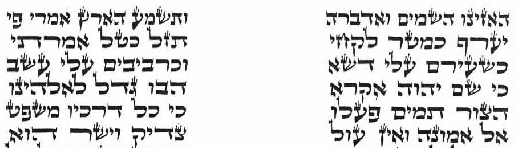

Also aesthetically, Haazinu stands out with its special two-column layout. In the modern Torahs, the two columns are perfectly even, like two towers, and usually are two pages long. I wanted to post a picture of the whole thing but I only found this one:

We find the same layout in the Megillat Esther, in which the ten sons of Haman are listed in the same fashion. Like in Haazinu, most sofrim (not me!) stretch the letters so every column will start and end in the same place:

But if you look in the old Torahs and in the Torahs of the Yemenite Jews you will see that the columns there aren't uniform at all. Below is a picture from a Yemenite tikkun:

I guess the Ashkenazi sofrim took the liberty to strectch the lines in order to make the scrolls look nicer, on the grounds of "zeh keli veanveiu".

But there's another thing that really puzzled me. Aside from the layout, the Yemenite scrolls also differ in the actual poem structure and that's the real reason why their columns aren't simetrical - there are less lines and thus some of the lines are longer.

For instance, look in the 17th line in the above picture, "zechor yemot olam.." - this is a long line. In the Ashkenzai scrolls this long line is divided in two, enabling our sofrim to justify the lines. Now that's odd! There are two other places where there's a difference in the poem structure but I will leave it for you to figure it out.

Which is the right structure?

That's where the Aleppo Codex comes to the scene. This is a topic for another post, but it suffices to say that the Aleppo Codex, guarded by the Aleppo Jews until 1948, is the most accurate Tikkun ever. Unfortunately, this Tikkun only covers the Nach; the Torah pages were mysteriously lost in a Arab riot in Aleppo. That is, all the Torah pages were lost besides..... that's right, the pages of Shirat Haazinu! And if you guessed that the Yemenite scrolls are identical to it, you are right. I got this image from the Aleppo Codex website:

This would imply that the Ahskenazi structure of Shirat Hazinu is problematic. Halacha says that if there's a pause (parsha setuma or petucha) in a wrong place, this will invalidate a Sefer Torah. If the Ashkenazi scrolls have a different poem structure, some of the open spaces are in the wrong place!

This would imply that the Ahskenazi structure of Shirat Hazinu is problematic. Halacha says that if there's a pause (parsha setuma or petucha) in a wrong place, this will invalidate a Sefer Torah. If the Ashkenazi scrolls have a different poem structure, some of the open spaces are in the wrong place!The answer is simple: the open spaces in Shirat Haazinu (and Az Yashir) are not open and separate Parshas, but a special layout of a song. The halachot of Parsha Petucha and Setuma don't apply here and whatever layout you have - Yemenite or Ashkenazi - will be Kosher for all intents and purposes. So although it's clear that the Yemenite arrangement is more reliable, you should not start complaining about our modern-day structure.

This is the story of the layout of Shirat Haazinu. I hope you enjoyed and I wish you a Gmar Hatima Tova!