In this series of posts, you will read about the few stories of Chazal that speak about Sta"m - Sefer Torah, Tefillin and Mezuzot. This story is about a Mezuza and a diamond gift (full disclosure: YK works with diamonds).

Yerushalmi Peah - Page 4, Chapter 1, Halacha 1:

Yerushalmi Peah - Page 4, Chapter 1, Halacha 1:

"Artevan (either a king or a wealthy Jew), sent to Rabbenu Hakadosh (Rabbi Judah the prince - 2nd century CE), the compiler of the Mishnah, a precious diamond as a gift, and requested that Rabbenu Hakadosh reciprocate by sending him a gift, equal to his. The Rabbi sent him a mezuzoh. Artevan asked him, "I sent you and invaluable diamond, and you send me a gift that is worth a half-shekel? Rabbenu Hakadosh replied, "My property (Rabbenu Hakadosh was very wealthy) and your property cannot pay the value of a mezuzoh, as King Solomon says in Proverbs: 'All your desirables cannot equal it.' Moreover, our riches we must guard, whereas the mezuzoh guards us."

The Sheiltot of Rabbi Achai, Parshat Ekev, adds another layer to the story:

And finally, in Yoma 11A:"Right after (Rebi sent the Mezuza), Artevan's only daughter fell seriously sick. He summoned the most skillful physicians, but no one could save her. Artevon then decided to heed to Rebi's advice and fix the Mezuza in his doorpost and his daughter got immediately cured."

"There was a story with Artevin, who was once checking the market's Mezuzot and got fined by the local authorities (who banned all Mezuzas)."Why was Artevin checking Mezuzas in the market? Some commentators say that after his daughter healed he took upon himself to make sure that every Jew would have a proper Mezuza at his doorpost, and he would go around checking them once a year.

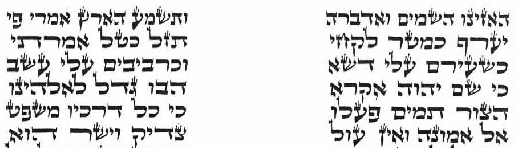

This would imply that the Ahskenazi structure of Shirat Hazinu is problematic. Halacha says that if there's a pause (

This would imply that the Ahskenazi structure of Shirat Hazinu is problematic. Halacha says that if there's a pause (